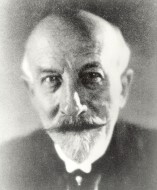

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès Georges Melies

French magician, filmmaker

French magician, filmmaker

At once the cinema's first true artist and the most prolific technical innovator of the early years, Georges Méliès was a pioneer in recognising the possibilities of the medium for narrative and spectacle. He created the basic vocabulary of special effects, and built the first studio of glass-house form, the prototype of European studios of the silent era. The success of his films contributed to the development of an international market in films and did much to secure the ascendancy of French cinema in the pre-1914 years. Outside this historical contribution, Méliès's films are the earliest to survive as a total, coherent artistic creation with its own validity and personality. They had a visual style as distinctive as Douanier Rousseau or Chagall, and a sense of fantasy, fun and nonsense whose exuberance is still infectious after almost a century. Méliès' parents had built up a prosperous footwear business and at twenty-one, after military service, Georges joined his elder brothers in the factory. Rescue from this mundane prospect came in 1884 when he was sent to London to learn English. He was enchanted by the London pantomimes, but much more by the magic shows of Maskelyne and Cooke at the Egyptian Hall, which inspired him to study stage illusionism. In 1888 his share of the family business, which his father had handed over to his sons, and a rich marriage, enabled him to take over the small but famous Parisian home of stage magic, the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, at 8 Boulevard des Italiens. Over the next decade Méliès devised some twenty-five major stage illusions, many of which were later to inspire his films.

Already a respected personality in the Parisian entertainment world, Méliès was naturally invited to the générale of the Lumière show at the Grand Café on 28 December 1895. Seeing in the Cinématographe a new attraction for his theatre, he attempted to buy it. When the Lumières refused him, he went to London to acquire one of Robert Paul's earliest projectors. This, with the aid of an engineer, Lucien Reulos, he converted into his first film camera. Able only to buy a stock of unperforated Eastman film, he was obliged to commission a perforator from a local engineer. In May 1896, a month after he had begun showing Paul and Edison films at his theatre, Méliès was able to shoot his first film Une Partie de Cartes. By September, with Reulos and Lucien Korsten, he patented a new camera, which was subsequently advertised as the Kinétographe Robert-Houdin. In December he adopted the Star trade mark. By the end of 1896 Méliès had shot eighty films, each twenty metres in length, and had already explored the effects that could be obtained by accelerated motion (in Dessinateur: Chamberlain) and substitution. He claimed that this effect, which was to be so basic to his work, was discovered one day when his camera jammed briefly while filming in la place de l'Opera: when the film was printed and screened, Méliès was thrilled to find that a motor bus had changed into a hearse. At once he perceived that the trick was a more effective means of producing the disappearance of a lady (L'Escamotage d'une dame chez Robert-Houdin) than the elaborate machinery of his stage illusions.

Early in 1897 Méliès constructed a studio a Montreuil-sous-Bois, in which he was able to elaborate his productions and trick work. In the course of the next few years he widened his repertoire of trickery with elaborate double and multiple exposures and effects of growing or diminishing figures produced by techniques analagous to the Phantasmagoria magic lantern. His productions also became more lavish in their use of costumes and fantastic or rococo decors, all painted by Méliès himself. his proudest achievement was the role he claimed as the creator of 'vues composées' - that is, mise-en-scenes rather than the actualities which were the regular subjects of the first film makers. Méliès was also a pioneer in assembling a number of 'films' or shots to tell a continuous story. This technique was analagous to the tableau style of magic lantern narrative rather than to modern notions of film editing; but in the years 1898-1900 it was a significant advance. Méliès's sheer variety was staggering. Apart from the trick films based on his stage illusions, his 500 films included dramatised actualities such as L'Affaire Dreyfus or The Coronation of King Edward VII, fairy stories (Cendrillon, Le petit Chaperon rouge), topical satires (Le Tunnel sous la Manche, Le Raid Paris-Monte Carlo en deux heures), social tracts (Les Incendiaires, La Civilization à travers les ages), historical subjects (Jeanne d'Arc, La Tour de Londres et les derniers moments d'Anne de Boleyn) and even adaptations of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar and Hamlet. Best-loved though are his comedy science fiction films in gentle parody of Jules Verne (Voyage dans la lune, Voyage à travers l'impossible, La Conquête du Pole).

Méliès's films won a world-wide market - and attracted world-wide plagiarism. His celebrity is attested by his choice as president of the Congrès international des Fabricants de Films held in Paris in 1909. The Congress however heralded a new era of the industry which would have no place for the pioneer, independent artist-artisans like Méliès. His trick work demanded a static camera; and this and his distinctive - and so unchanging - graphic vision seemed archaic in the era of D.W. Griffith. He signed a distribution contract with Pathé, ceding his independence: soon his film activity came to an end. The war of 1914 brought other troubles. His wife had died in 1913. His brother Gaston, who had run an American branch of the firm which had eventually seceded, died in 1915. The Théatre Robert-Houdin was closed by the War and eventually swept away by urban development. Méliès turned his studio into a theatre, but by 1923 that too had failed and the property was sold, along with all the scenery, props and costumes from the films. About the same time, with nowhere to store them, he ordered the destruction of all his negatives. Now penniless, he married his former actress and long-time mistress Jehanne d'Alcy. They lived from the proceeds of a tiny boutique selling toys and novelties on the Gare Montparnasse: this period was, said Méliès later, 'a true martyrdom'. Rediscovered by a new generation of film enthusiasts in the early thirties, this great pioneer was belatedly feted, and eventually he and his wife were given a place in the home for cinema veterans at the Chateau d'Orly, where he spent his final days seemingly contented, still drawing, reminiscing and occasionally performing little conjuring tricks.

David Robinson